"Creating Tumoroids In VR"

Virtual Reality (VR) and 3D technologies are widely used in various fields such as medicine, education and bioinformatics. In particular, it has shown great potential for application in biomedical data visualisation. Although existing research has addressed several aspects of this technology, there are still many challenges associated with virtual reality in the field of biomedical data visualisation. This study focuses on exploring the latest applications within the biomedical field and examines how Virtual Reality Learning Environments (VRLE) can provide novel insights and a deeper understanding of tumour biology.

In building the BioVirt Lab platform, we describe in detail the design ideas, development process, experimental design, and data evaluation guidelines of the platform. The development of the BioVirt Lab went through four key stages: preliminary research, data collection and processing, visual modelling and scenario building of the data, and development of the VR application.

In building the BioVirt Lab platform, we describe in detail the design ideas, development process, experimental design, and data evaluation guidelines of the platform. The development of the BioVirt Lab went through four key stages: preliminary research, data collection and processing, visual modelling and scenario building of the data, and development of the VR application.

1. Introduction

1.1 Tumour biology and microenvironment

With the rapid development of medical science and technology, cancer research has been at the forefront of efforts to find more effective methods of prevention, diagnosis and treatment. According to statistics, millions of people around the world are diagnosed with cancer every year, which makes cancer one of the leading causes of death worldwide. Cancer is not just a health issue; it has a huge impact on economies, societies and families around the globe. To address this worldwide challenge, it has become crucial to understand the biology of tumours and their microenvironment.

A tumour is not an isolated entity; it is intimately connected to its surroundings. Tumour cells interact with their surrounding cells, stroma, blood vessels and immune cells to form a complex "ecosystem". Each part of this system affects tumour progression, aggressiveness and response to therapy[1]. In addition, factors in the tumour microenvironment, such as hypoxia, acidity and immunosuppression, pose challenges to tumour treatment, which is why more complex models are needed to simulate real-life situations.

It is due to this complexity that traditional two-dimensional (2D) cell culture methods are limited in their ability to simulate the real tumour microenvironment. While 2D culture has provided us with a great deal of valuable information in the past, it cannot fully reproduce the three-dimensional structure of a tumour and its interaction with the microenvironment.

1.2 The Rise of Bionic 3D Tumour Modelling

Given these limitations, bionic 3D tumour models have become a focus of research. Compared to 2D cultures, 3D models provide a more realistic platform that allows cells to grow, differentiate and migrate in three dimensions, better mimicking the real tumour microenvironment[2]. These models can simulate not only tumour growth but also drug delivery and metabolism, providing new opportunities for drug screening and personalised therapy.

However, the complexity of such models also brings new challenges to researchers. Observing and interpreting these models requires a high degree of skill and in-depth knowledge in order to construct three-dimensional cell structures from two-dimensional images as well as to accurately depict the dynamic properties of tumour cells. Especially when it comes to analysing cell structure and behaviour through microscopy, researchers are required to have strong spatial thinking skills.

1.3 Application and Prospects of Virtual Reality Technology in Biomedical 3D Model Data Visualisation

![]()

![]()

As life sciences become more and more dependent on data science, visualisation becomes crucial, especially for data from advanced experimental techniques such as 3D genomics, spatial transcriptomics and macro-genomics[3]. When it comes to VR tools in this field, there are two main types: one is called Non Imaging Examples, and the other is called Imaging Examples. Today, we mainly talk about Non Imaging Examples. The main task of this type of tool is to turn cell data into a 3D form, like a "map" of cells. Over the past two decades, life science data has grown in volume and complexity, making data analysis a significant bottleneck. With rapid advances in computer science and technology as well as graphics, Virtual Reality (VR) has become an important tool in science, industry, and economics, especially in the "Metaverse Evidence Wall" of biomedical engineering data visualisation[4].

![]()

To help researchers better understand 3D tumour models, we propose the use of virtual reality (VR) technology. Virtual reality (VR) provides an immersive environment that allows users to observe and analyse models from all angles[5]. The introduction of this technology not only helps researchers to understand complex 3D structures more intuitively but also provides new ideas for experimental design by simulating experiments such as drug delivery and cell migration.

In addition, virtual reality (VR) technology offers a new way to visualise 3D tissue data in biomedical research. For example, one study used virtual reality (VR) to create a new interface for breast cancer research that can be used to visualise 3D tissue data, thus providing a new approach to cancer research[6]. However, the development and research of virtual reality (VR) platforms for microscopic 3D visualisation of cancer cells has been relatively limited. Indeed, the use of virtual reality (VR) technology is expected to greatly enhance researchers' understanding of 3D models. This is not only because virtual reality (VR) provides a 360-degree viewing perspective, but more importantly, it allows researchers to interact with the models and explore cellular interactions in depth.

1.3 Application and Prospects of Virtual Reality Technology in Biomedical 3D Model Data Visualisation

As life sciences become more and more dependent on data science, visualisation becomes crucial, especially for data from advanced experimental techniques such as 3D genomics, spatial transcriptomics and macro-genomics[3]. When it comes to VR tools in this field, there are two main types: one is called Non Imaging Examples, and the other is called Imaging Examples. Today, we mainly talk about Non Imaging Examples. The main task of this type of tool is to turn cell data into a 3D form, like a "map" of cells. Over the past two decades, life science data has grown in volume and complexity, making data analysis a significant bottleneck. With rapid advances in computer science and technology as well as graphics, Virtual Reality (VR) has become an important tool in science, industry, and economics, especially in the "Metaverse Evidence Wall" of biomedical engineering data visualisation[4].

To help researchers better understand 3D tumour models, we propose the use of virtual reality (VR) technology. Virtual reality (VR) provides an immersive environment that allows users to observe and analyse models from all angles[5]. The introduction of this technology not only helps researchers to understand complex 3D structures more intuitively but also provides new ideas for experimental design by simulating experiments such as drug delivery and cell migration.

In addition, virtual reality (VR) technology offers a new way to visualise 3D tissue data in biomedical research. For example, one study used virtual reality (VR) to create a new interface for breast cancer research that can be used to visualise 3D tissue data, thus providing a new approach to cancer research[6]. However, the development and research of virtual reality (VR) platforms for microscopic 3D visualisation of cancer cells has been relatively limited. Indeed, the use of virtual reality (VR) technology is expected to greatly enhance researchers' understanding of 3D models. This is not only because virtual reality (VR) provides a 360-degree viewing perspective, but more importantly, it allows researchers to interact with the models and explore cellular interactions in depth.

2. BioVirt Lab

This research is dedicated to the design and development of an interactive immersive virtual reality learning platform - BioVirt Lab. The development process encompasses crucial sub-phases such as preliminary research, data collection, processing, data visualization modeling and scene modeling, and virtual reality (VR) development. The data used in this project originates from the London University Health and Disease 3D Model Center, while the data processing was a collaborative effort between that center and the Wellcome Trust Human Genetics Center at the University of Oxford. During the modeling phase, besides employing Blender for simulating cell morphology, I also utilized real data to perform data modeling using Blender (Python), engaging in an in-depth exploration of encountered challenges and their corresponding strategies for resolution. Subsequently, I constructed highly realistic three-dimensional tumor models using Unity3D and created animated visualizations depicting the growth of tumors in the surrounding extracellular matrix. Moreover, based on the actual settings of the UCL Bioengineering Laboratory, I reconstructed the laboratory model within Unity. This model was ultimately employed as the teaching and experimental environment for BioVirt Lab, providing simulated experimental scenarios for future research on the effectiveness of virtual reality technology in improving the understanding and cognition of complex three-dimensional tumor microenvironments.

2. BioVirt Lab

This research is dedicated to the design and development of an interactive immersive virtual reality learning platform - BioVirt Lab. The development process encompasses crucial sub-phases such as preliminary research, data collection, processing, data visualization modeling and scene modeling, and virtual reality (VR) development. The data used in this project originates from the London University Health and Disease 3D Model Center, while the data processing was a collaborative effort between that center and the Wellcome Trust Human Genetics Center at the University of Oxford. During the modeling phase, besides employing Blender for simulating cell morphology, I also utilized real data to perform data modeling using Blender (Python), engaging in an in-depth exploration of encountered challenges and their corresponding strategies for resolution. Subsequently, I constructed highly realistic three-dimensional tumor models using Unity3D and created animated visualizations depicting the growth of tumors in the surrounding extracellular matrix. Moreover, based on the actual settings of the UCL Bioengineering Laboratory, I reconstructed the laboratory model within Unity. This model was ultimately employed as the teaching and experimental environment for BioVirt Lab, providing simulated experimental scenarios for future research on the effectiveness of virtual reality technology in improving the understanding and cognition of complex three-dimensional tumor microenvironments.

2.1 The core concept of BioVirt Lab

As the 21st century unfolds, the life sciences field will increasingly rely on innovative tools and methods in data science[38]. Data visualization, also known as DataVis, is one such core technology that can transform complex data and analysis results into profound insights[39]. However, scientific knowledge is inherently abstract and complex, involving phenomena that cannot be directly observed and extreme scales, which poses significant challenges in understanding scientific concepts[30]. Nowadays, the rise of virtual reality technology has allowed researchers in the fields of biology and chemistry to magnify microscale 3D entities, such as organelles and their functions[31][32]

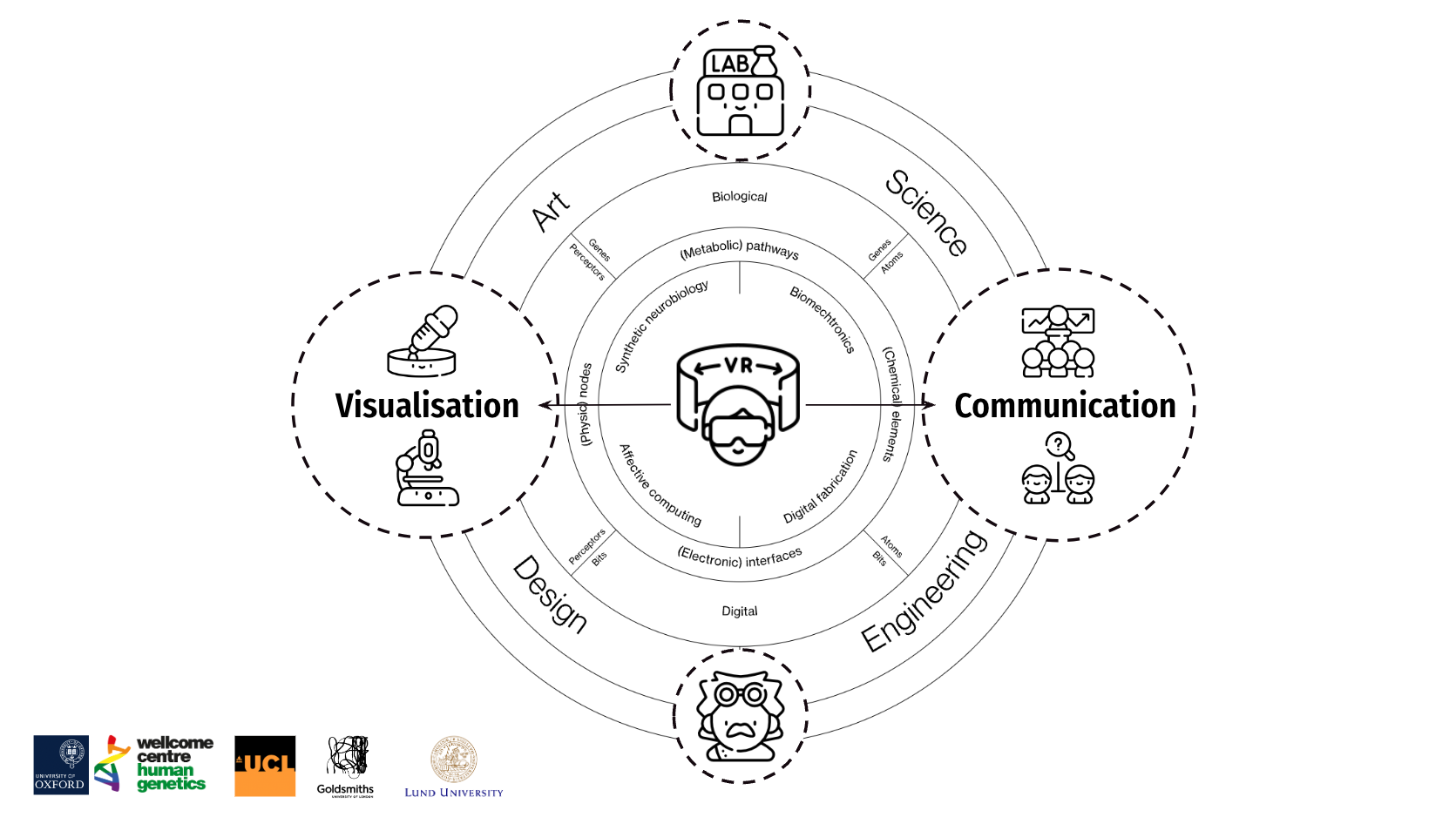

Against this backdrop, the virtual reality (VR) project of the BioVirt Lab places greater emphasis on the free-form exploration of scientific data, rather than solely pursuing speed and accuracy in task completion. My design and development adhere to three core concepts: the artistic representation of scientific knowledge, and the direct visualization of data or mixed data presentation, which encompasses multiple sources of data designed for virtual reality (VR) spaces, such as data from electron microscopes and fluorescence microscopes. This artistic display can be compared to the charts in textbooks, as they both aim to convey a deep understanding of specific phenomena.

2.2 From 2D to VR

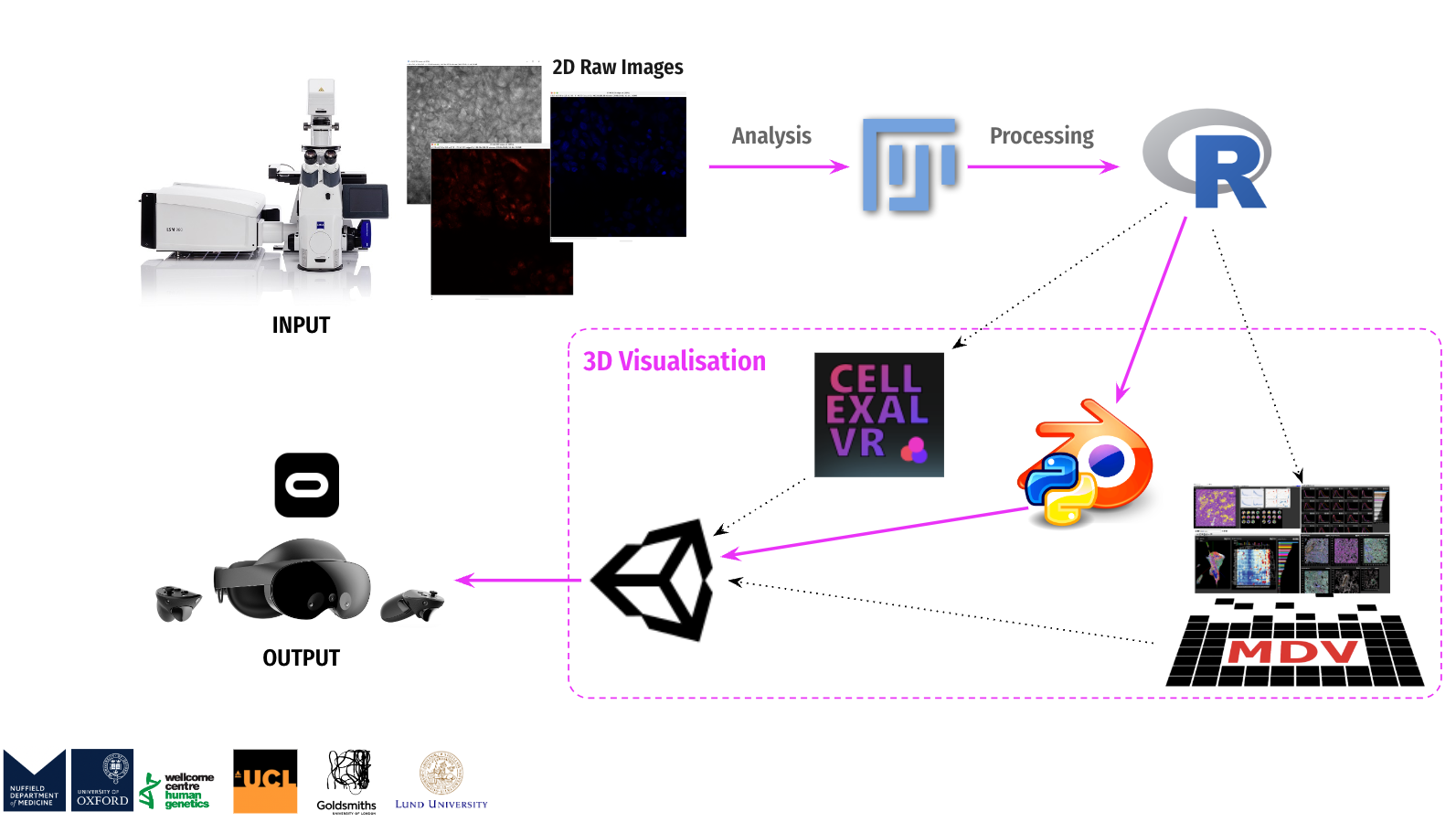

My development process is divided into four core stages: preliminary research, data collection and processing, data visualization modeling and scene construction, and virtual reality (VR) development. All the data used in the project is sourced from the 3D Model Centre for Health and Disease at the University of London. Additionally, the data processing work is carried out collaboratively by the center and the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics at the University of Oxford. During the modeling stage, I will use Blender to simulate cell morphology and combine real data through Python scripts in Blender for data modeling. Next, I will use Unity3D to create a realistic 3D tumor model and design a visualization animation depicting tumor growth. Furthermore, I have referred to the actual environment of the UCL Bioengineering Lab and created a laboratory model in Unity, which will be integrated into the BioVirt Lab to provide an experimental scenario for studying the effects of virtual reality (VR) technology in enhancing understanding of complex 3D tumor microenvironments.

The pink line shows my development path.

2.3 Preliminary Research

To clarify the requirements, we organised several team discussions at the early stage of the projet, which not only covered the overall framework and objectives of the project but also explored the details in depth to ensure a clear understanding of the project. In addition, to have a more comprehensive understanding of the background and requirements of the bionic 3D tumour model, I have systematically collected and analysed relevant project information. In order to experience and understand the actual application scenarios of the project more realistically, we also conducted experimental field observations, organised Open brush VR Experience Workshops and conducted interviews with experts in the field of bioengineering and actual users. These field experiences and exchanges enabled us to gain a deeper understanding of interdisciplinary knowledge, to concretise and organise the originally abstract concepts and requirements, and to lay a solid foundation for the subsequent development work.

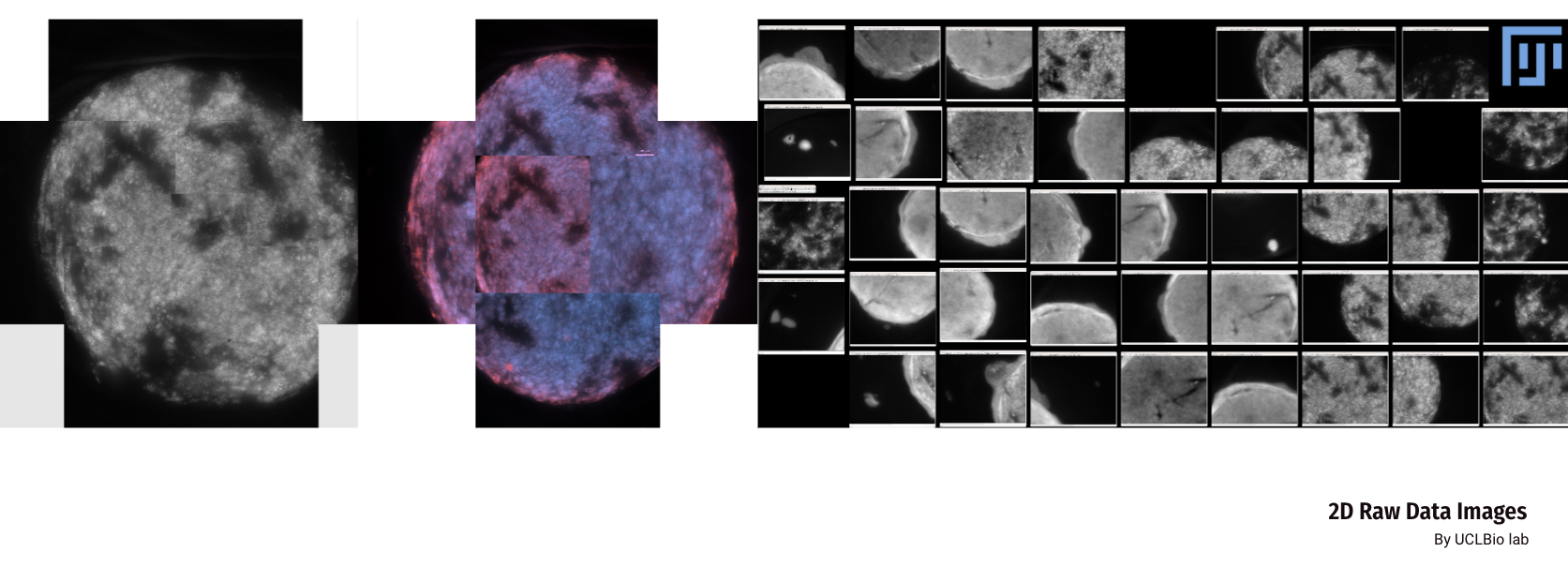

2.3 Data collection and processing

We collected two sets of image data for the bionic 3D tumour model: confocal images and non-confocal images. Confocal images were taken using a 10x or 20X objective lens, which provides finer image details. The non-confocal images, on the other hand, are taken clockwise at a magnification of 2.5× and are intended to capture a macroscopic view of tumour invasion. The image software used to view these data was Fuji.

For further analysis, we divided the data into two groups. the C control group was characterised by a higher activity of cancer cells, meaning that these cells were more likely to proliferate and spread. While the T-treated group had relatively low activity of cancer cells, which could be due to some treatment or other factors. This categorisation helps us to better understand and compare the differences between the different groups.

For further analysis, we divided the data into two groups. the C control group was characterised by a higher activity of cancer cells, meaning that these cells were more likely to proliferate and spread. While the T-treated group had relatively low activity of cancer cells, which could be due to some treatment or other factors. This categorisation helps us to better understand and compare the differences between the different groups.

2.4 3D Bionic Tumour Cell Model Development

The image on the left is a microscopic image of a cell that was processed to obtain a point cloud of the tumour-like body. The data is very noisy, so a thresholding method was used to make the data contain X, Y, and Z coordinates, and a QuPath was used to extract the coordinates of each Z layer, with Z being a "pseudo-depth" based on the Z-index (0- -8), which was multiplied by 100. X and Y are micrometres, so there is a gap of 100 micrometres between each layer.

When it comes to cancer cell data, it is common to focus on the features of the cells, and how these features correlate with factors such as cancer type, grade, and so on. By analysing the CSV files, here are a few possible scenarios for combining features:

When it comes to cancer cell data, it is common to focus on the features of the cells, and how these features correlate with factors such as cancer type, grade, and so on. By analysing the CSV files, here are a few possible scenarios for combining features:

In cancer cell data analysis, the focus is often on cell features and their correlation with factors like cancer type and grade. By examining the CSV files, several combinations of features can be considered:

1. Basic Cellular Characteristics: This includes the nucleus and cell area, perimeter, circularity, eccentricity, along with cytoplasm channel means (Ch1, Ch2). This combination helps determine cell shape, size, and cytoplasmic channel expression.

2. Nucleus-Cell Relationship Characteristics: Involves the area and circularity of both the nucleus and the cell, providing insights into their relationship.

3. Nucleus/Cell Area Ratio: This focuses on the ratio between nucleus and cell areas, which may indicate abnormal cancer cell morphology.

4. Multichannel Characterization: This uses mean values from multiple channels (Ch1, Ch2) for the nucleus, cell, and cytoplasm to capture more detailed characteristics.

Due to limitations in data volume (n=371K) and computational resources, I made several adjustments to the model, downscaling the sample size and selecting 2K samples. Ultimately, I found that nucleus-cell relationship features were best suited for the modelling task.

1. Basic Cellular Characteristics: This includes the nucleus and cell area, perimeter, circularity, eccentricity, along with cytoplasm channel means (Ch1, Ch2). This combination helps determine cell shape, size, and cytoplasmic channel expression.

2. Nucleus-Cell Relationship Characteristics: Involves the area and circularity of both the nucleus and the cell, providing insights into their relationship.

3. Nucleus/Cell Area Ratio: This focuses on the ratio between nucleus and cell areas, which may indicate abnormal cancer cell morphology.

4. Multichannel Characterization: This uses mean values from multiple channels (Ch1, Ch2) for the nucleus, cell, and cytoplasm to capture more detailed characteristics.

Due to limitations in data volume (n=371K) and computational resources, I made several adjustments to the model, downscaling the sample size and selecting 2K samples. Ultimately, I found that nucleus-cell relationship features were best suited for the modelling task.

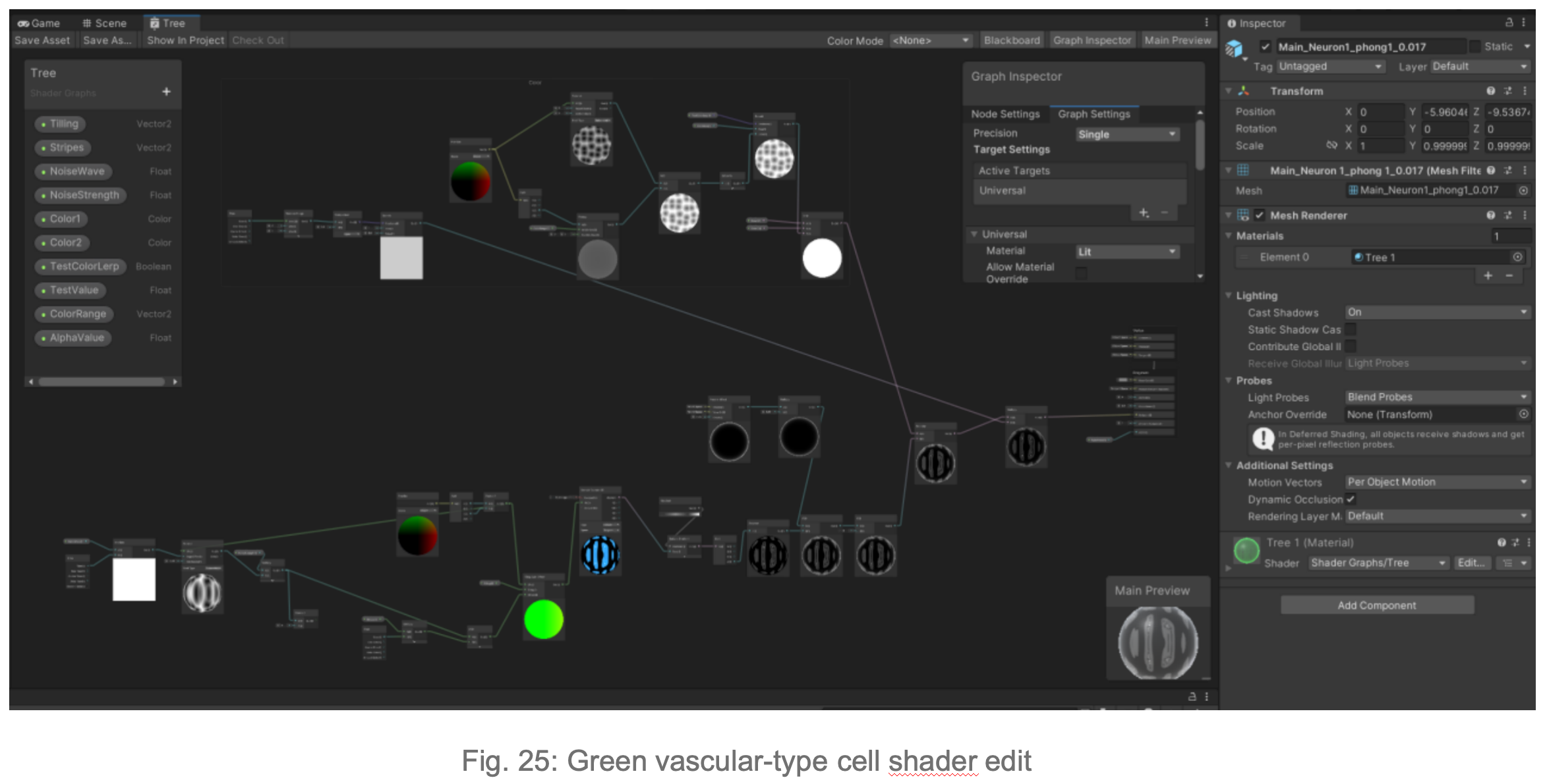

2.5 Simulation of Cell Morphology Modelling

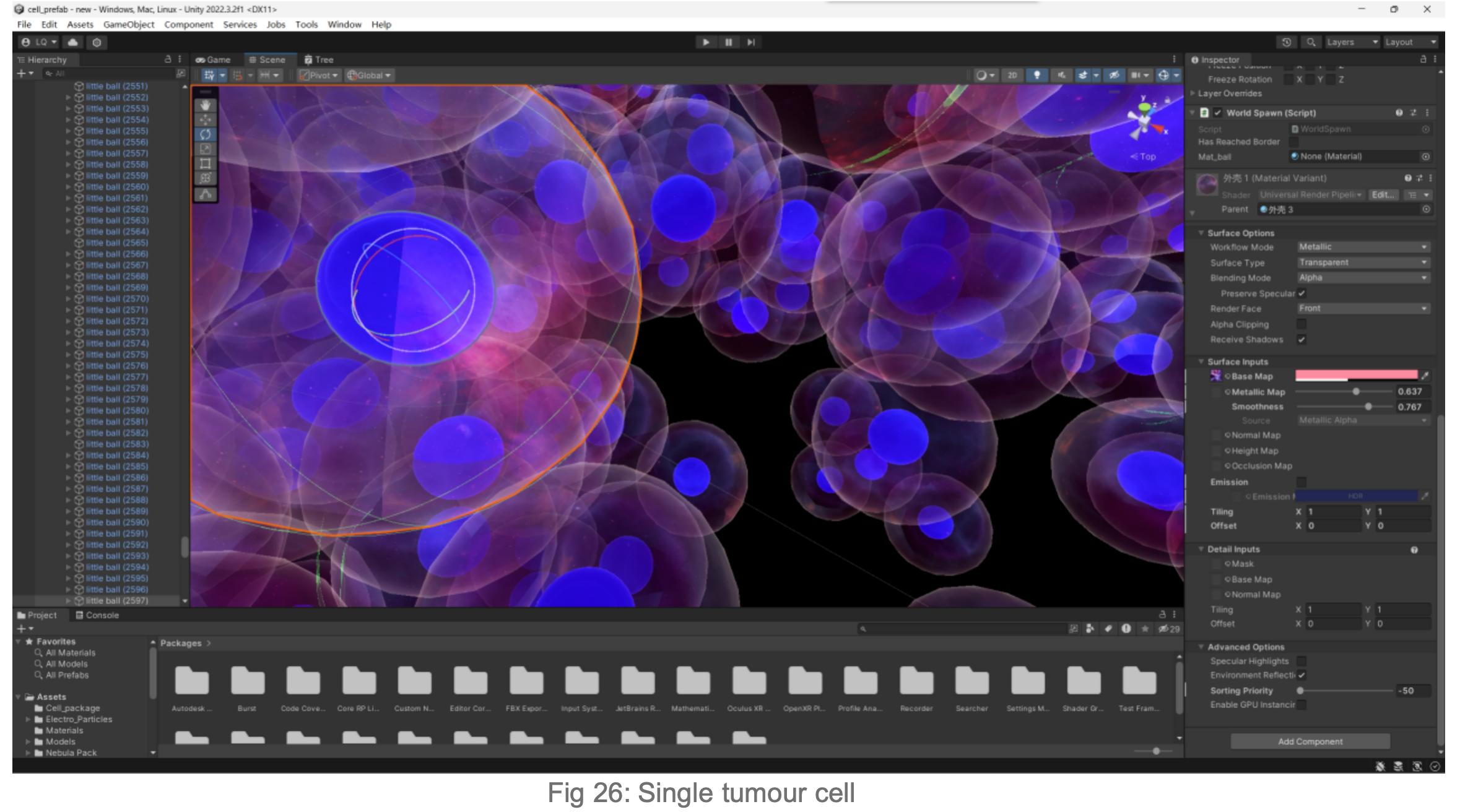

Due to issues with importing the model into Unity, I opted to create a highly realistic 3D tumor model directly in Unity3D. In this step, I focused on using morphological principles to create volume rendering, 3D mesh creation, shaders, and lighting (brightness parameters) to model different cell types in the biomimetic 3D tumor cell model. I actively communicated with the researchers to ensure the accuracy of the visualization.

In Blender, to simulate the fibrous morphology of CD31 endothelial cells, I employed vertex control methods and combined them with vector calculations to precisely control the simulation effects of particles.

To simulate the clustering phenomenon of cancer cells, I used dynamic adhesion simulation techniques in Blender and combined them with physical property settings to ensure the interaction and cohesion of cells.

In Unity3D, I built a three-dimensional tumor model that encompasses over 10,000 individual cell bodies, reflecting the complex structure and characteristics of tumors. To ensure accurate and intuitive data visualization, I tried and applied various visualization techniques, such as advanced shader techniques and mesh deformation techniques, aiming to enhance the realism and detail representation of the model.

2.6

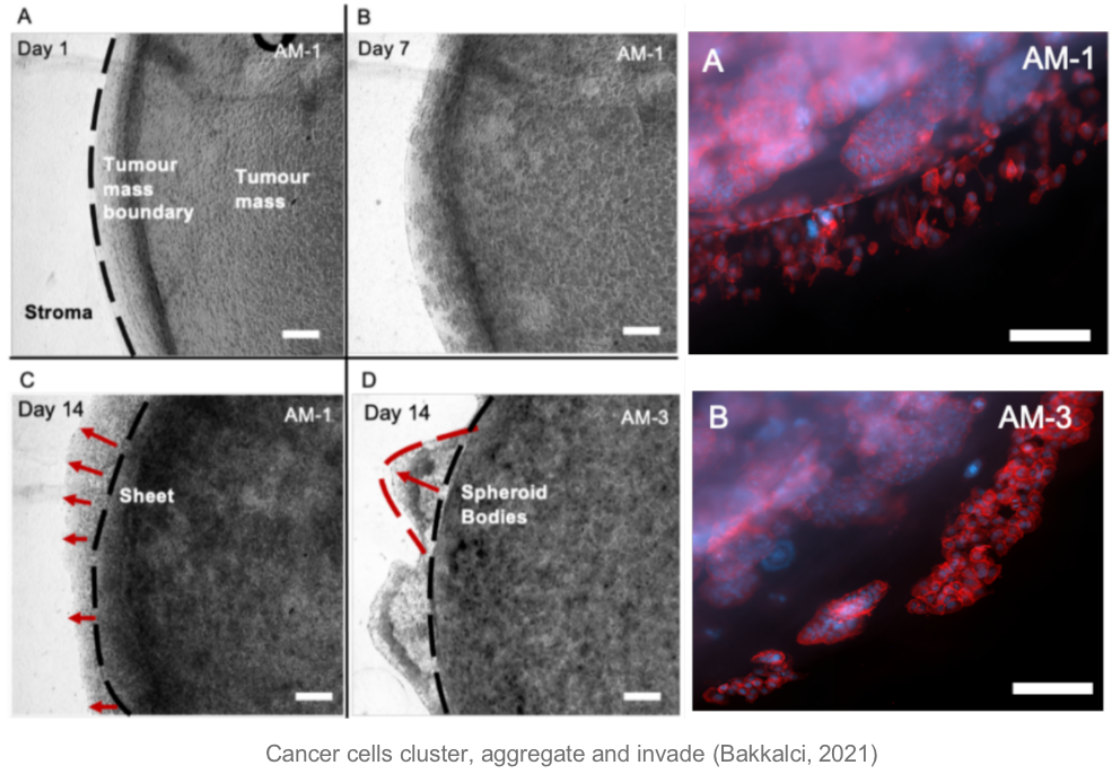

Animation of the growth of the tumour model into the surrounding stroma

The figure below shows that over time, the behaviour of the tumour cells in the orb mimics their natural behaviour in the human body: they cluster, aggregate and invade. When animating the growth of the tumour into the surrounding stroma, I specifically considered the user's perception of colour and intuitive manipulation of space in Virtual Reality (VR).

By observing and analysing the changes and interactions of the stromal cells, we were able to delve into the complexity of the tumour ecosystem. The completed 3D animations can be played back in virtual reality, which not only allows these animation resources to be reused multiple times but also in multiple presentations. Although these animations may not fully reflect the scientific facts, we have endeavoured to ensure transparency in their content and have added rich interactive elements to the virtual reality environment to enhance the user experience.

A. Difficulties:

From the interviews, we learned that it is extremely challenging to continuously observe the movement trajectories of cancer cells through a microscope. Therefore, when creating the cell growth animation, we mainly relied on subject knowledge and laboratory experience for speculation and simulation.

B. Solution:

![]()

![]()

1. The core of the animation is to show the design of the vascular network in the stromal compartment, simulating how cancer cells "hijack" the body's vascular network in order to obtain the required nutrients. We animated the tumour growth process from day 0 to day 21 to virtually represent the cellular interactions and dynamics in the tumour microenvironment.

2. In order to ensure the accuracy and realism of the growth animation of the tumour model and its surrounding matrix, I introduced a series of adjustable parameters. The purpose of these parameters is to correct potentially misleading visual cues, as well as to avoid visual confusion due to clashes and ghosting between visual elements. To enhance the three-dimensionality and depth of the scene, a variety of visual depth cueing techniques were used:

(1) Visual elements such as colour, blur, relative size, dynamics, background, occlusion and texture were used to enhance the realism of the scene. For example, the dead cancer cells gradually turn grey over time to simulate their changing process in the real environment.

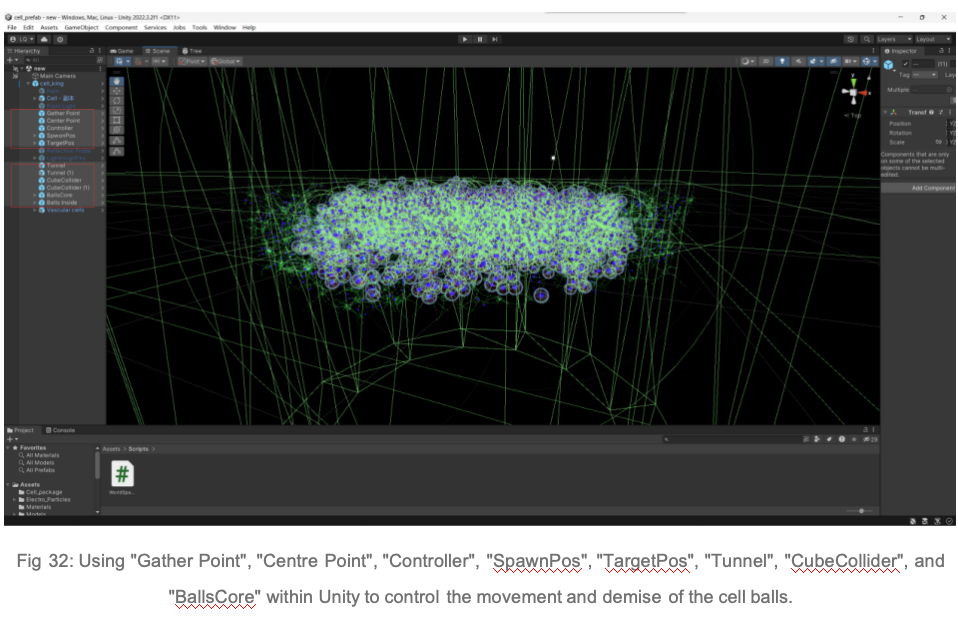

(2) Use the tools "Gather Point", "Center Point", "Controller", "SpawnPos", "TargetPos", "Tunnel", "CubeCollider", and "BallsCore" to accurately control the trajectories and behaviours of the cells to ensure that their movement patterns match the behaviour of real cells.

(3) I avoided the use of cues that could lead to visual conflicts and designed natural transitions and breaks in the animation presentation. This was done to ensure that the animation was presented in a way that was fully consistent with the observations and behaviours of the researchers in the experiments with the bionic 3D tumour model, thus providing a presentation that was both accurate and intuitive.

From the interviews, we learned that it is extremely challenging to continuously observe the movement trajectories of cancer cells through a microscope. Therefore, when creating the cell growth animation, we mainly relied on subject knowledge and laboratory experience for speculation and simulation.

B. Solution:

1. The core of the animation is to show the design of the vascular network in the stromal compartment, simulating how cancer cells "hijack" the body's vascular network in order to obtain the required nutrients. We animated the tumour growth process from day 0 to day 21 to virtually represent the cellular interactions and dynamics in the tumour microenvironment.

2. In order to ensure the accuracy and realism of the growth animation of the tumour model and its surrounding matrix, I introduced a series of adjustable parameters. The purpose of these parameters is to correct potentially misleading visual cues, as well as to avoid visual confusion due to clashes and ghosting between visual elements. To enhance the three-dimensionality and depth of the scene, a variety of visual depth cueing techniques were used:

(1) Visual elements such as colour, blur, relative size, dynamics, background, occlusion and texture were used to enhance the realism of the scene. For example, the dead cancer cells gradually turn grey over time to simulate their changing process in the real environment.

(2) Use the tools "Gather Point", "Center Point", "Controller", "SpawnPos", "TargetPos", "Tunnel", "CubeCollider", and "BallsCore" to accurately control the trajectories and behaviours of the cells to ensure that their movement patterns match the behaviour of real cells.

(3) I avoided the use of cues that could lead to visual conflicts and designed natural transitions and breaks in the animation presentation. This was done to ensure that the animation was presented in a way that was fully consistent with the observations and behaviours of the researchers in the experiments with the bionic 3D tumour model, thus providing a presentation that was both accurate and intuitive.

2.7

BioVirt Lab Scenario Construction

Virtual Reality Learning Environments (VRLEs) offer significant advantages for science education. It allows learners to explore and experience scientific concepts in an intuitive, concrete way, rather than just understanding abstract scientific knowledge by dealing with equations, formulas, or other symbolic representations. For example, students can immerse themselves in a human cell and look around in a three-dimensional perspective to visualise the various organelles and structures within the cell[42]. This three-dimensional visualisation of scientific phenomena not only supports students' conceptual learning but also contributes to the development of their spatial knowledge and skills[43].Notably, the scenario design of BioVirt Lab is based on the real environment of the UCL Bioengineering Laboratory, ensuring its authenticity and practicality.

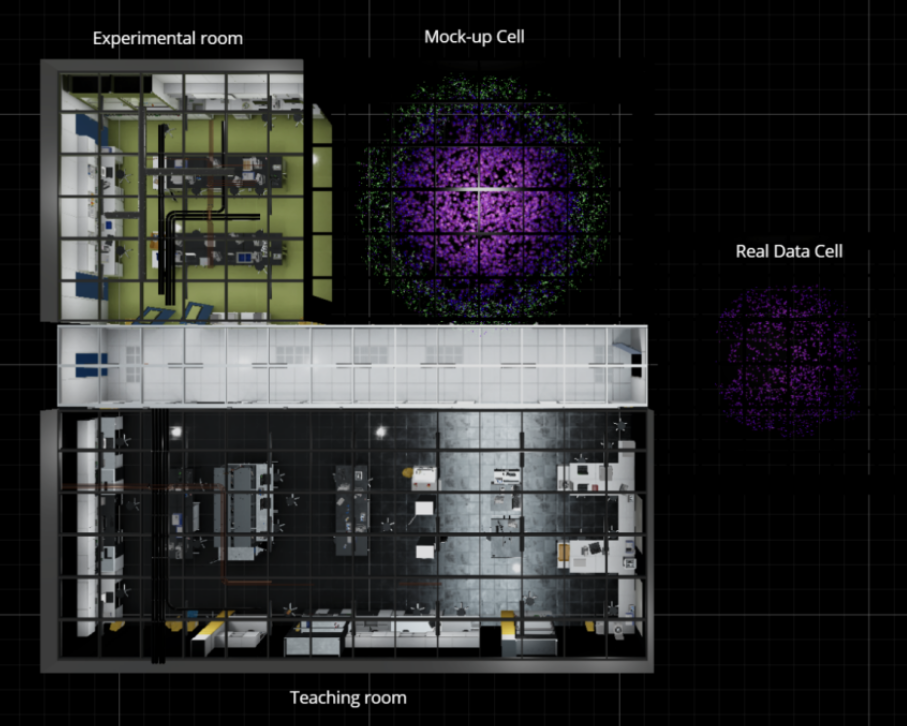

BioVirt Lab is a comprehensive virtual laboratory, which mainly consists of a teaching area, an experimental manipulation area, a microscopic cell display area and a real data display area. In the microscopic cell display area and the real data display area, students can observe in detail the various components of a tumour cell, such as the nucleus, cytoplasm and stromal cells. These highly detailed 3D models provide an intuitive platform for students to help them gain a deeper understanding of cell structure and function. In addition, this interactive learning experience also helps to enhance students' spatial cognitive skills.

3.

References

3.1 Literature:

3.

References

3.1 Literature:

[1] Y. Zhu, E. Kang, M. Wilson, T. Basso, E. Chen, Y. Yu, and Y. R. Li, "3D tumor spheroid and organoid to model tumor microenvironment for cancer immunotherapy," Organoids, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 149-167, 2022.

[2] J. Pape, M. Emberton, and U. Cheema, "3D cancer models: the need for a complex stroma, compartmentalization and stiffness," Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, vol. 9, p. 660502, 2021.

[3] S. I. O'Donoghue, "Grand challenges in bioinformatics data visualization," Frontiers in Bioinformatics, vol. 1, p. 669186, 2021.

[4] S. Taylor and S. Soneji, "Bioinformatics and the Metaverse: Are we ready?," Frontiers in Bioinformatics, vol. 2, p. 50, 2022.

[5] A. V. Reinschluessel, T. Muender, D. Salzmann, T. Doering, R. Malaka, and D. Weyhe, "Virtual reality for surgical planning–evaluation based on two liver tumor resections," Frontiers in Surgery, vol. 9, p. 821060, 2022.

[6] D. Bressan, C. M. Mulvey, F. Qosaj, R. Becker, F. Grimaldi, S. Coffey, S. L. Vogl, L. Kuett, R. Catena, A. Dariush, and C. Gonzalez-Fernandez, "Exploration and analysis of molecularly annotated, 3D models of breast cancer at single-cell resolution using virtual reality," bioRxiv, pp. 2021-06, 2021.

[7] K. C. Cassidy, J. Šefčík, Y. Raghav, A. Chang, and J. D. Durrant, "ProteinVR: Web-based molecular visualization in virtual reality," PLoS computational biology, vol. 16, no. 3, p. e1007747, 2020.

[8] S. González Izard, R. Sánchez Torres, O. Alonso Plaza, J. A. Juanes Mendez, and F. J. García-Peñalvo, "Nextmed: automatic imaging segmentation, 3D reconstruction, and 3D model visualization platform using augmented and virtual reality," Sensors, vol. 20, no. 10, p. 2962, 2020.

[9] Bressan, C. M. Mulvey, F. Qosaj, R. Becker, F. Grimaldi, S. Coffey, S. L. Vogl, L. Kuett, R. Catena, A. Dariush, and C. Gonzalez-Fernandez, "Exploration and analysis of molecularly annotated, 3D models of breast cancer at single-cell resolution using virtual reality," bioRxiv, pp. 2021-06, 2021.

[10] Legetth, J. Rodhe, S. Lang, P. Dhapola, M. Wallergård, and S. Soneji, "CellexalVR: A virtual reality platform to visualize and analyze single-cell omics data," IScience, vol. 24, no. 11, 2021.

[11] F. Huettl, P. Saalfeld, C. Hansen, B. Preim, A. Poplawski, W. Kneist, H. Lang, and T. Huber, "Virtual reality and 3D printing improve preoperative visualization of 3D liver reconstructions—results from a preclinical comparison of presentation modalities and user’s preference," Annals of translational medicine, vol. 9, no. 13, 2021.

[12] I. Lau, A. Gupta, and Z. Sun, "Clinical value of virtual reality versus 3D printing in congenital heart disease," Biomolecules, vol. 11, no. 6, p. 884, 2021.

[13] K. A. Demidova and N. Markovkina, "Technologies of Virtual and Augmented Reality in Biomedical Engineering," in 2022 Conference of Russian Young Researchers in Electrical and Electronic Engineering (ElConRus), pp. 1496-1499, Jan. 2022.

[14] A. Elor, S. Whittaker, S. Kurniawan, and S. Michael, "BioLumin: An Immersive Mixed Reality Experience for Interactive Microscopic Visualization and Biomedical Research Annotation," ACM Transactions on Computing for Healthcare, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 1-28, 2022.

[15] E. Pajorová, L. Hluchý, I. Kostič, J. Pajorová, M. Bačáková, and M. Zatloukal, "A virtual reality visualization tool for three-dimensional biomedical nanostructures," in Journal of Physics: Conference Series, vol. 1098, no. 1, p. 012001, Sep. 2018.

[16] I. J. Akpan and M. Shanker, "A comparative evaluation of the effectiveness of virtual reality, 3D visualization and 2D visual interactive simulation: an exploratory meta-analysis," Simulation, vol. 95, no. 2, pp. 145-170, 2019.

[17] I. J. Akpan, M. Shanker, and R. Razavi, "Improving the success of simulation projects using 3D visualization and virtual reality," Journal of the Operational Research Society, vol. 71, no. 12, pp. 1900-1926, 2020.

[18] K. Betts, P. Reddy, T. Galoyan, B. Delaney, D. L. McEachron, K. Izzetoglu, and P. A. Shewokis, "An Examination of the Effects of Virtual Reality Training on Spatial Visualization and Transfer of Learning," Brain Sciences, vol. 13, no. 6, p. 890, 2023.

[19] W. Yin, "An artificial intelligent virtual reality interactive model for distance education," Journal of Mathematics, 2022, pp. 1-7.

[20] H. Roh, J. W. Oh, C. K. Jang, S. Choi, E. H. Kim, C. K. Hong, and S. H. Kim, "Virtual dissection of the real brain: integration of photographic 3D models into virtual reality and its effect on neurosurgical resident education," Neurosurgical Focus, vol. 51, no. 2, p. E16, 2021.

[21] J. Pape, T. Magdeldin, M. Ali, C. Walsh, M. Lythgoe, M. Emberton, and U. Cheema, "Cancer invasion regulates vascular complexity in a three-dimensional biomimetic model," European Journal of Cancer, vol. 119, pp. 179-193, 2019.

[22] H. K. Wu and P. Shah, "Exploring visuospatial thinking in chemistry learning," Science Education, vol. 88, no. 3, pp. 465-492, 2004.

[23] T. Timonen et al., "Virtual reality improves the accuracy of simulated preoperative planning in temporal bones: a feasibility and validation study," European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, vol. 278, pp. 2795-2806, 2021.

[24] L. Kuett et al., "Three-dimensional imaging mass cytometry for highly multiplexed molecular and cellular mapping of tissues and the tumor microenvironment," Nature Cancer, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 122-133, 2022.

[25] F. Biocca and B. Delaney, "Immersive virtual reality technology," Communication in the Age of Virtual Reality, vol. 15, no. 32, pp. 10-5555, 1995.

[26] C. Dede, "Immersive interfaces for engagement and learning," Science, vol. 323, no. 5910, pp. 66-69, 2009.

[27] A. Dengel and J. Mägdefrau, "Immersive learning explored: Subjective and objective factors influencing learning outcomes in immersive educational virtual environments," in 2018 IEEE International Conference on Teaching, Assessment, and Learning for Engineering (TALE), pp. 608-615, Dec. 2018.

[28] S. Schwan, "Digital pictures, videos, and beyond: Knowledge acquisition with realistic images," The Psychology of Digital Learning: Constructing, Exchanging, and Acquiring Knowledge with Digital Media, pp. 41-59, 2017.

[29] M. El Beheiry et al., "Virtual reality: beyond visualization," Journal of Molecular Biology, vol. 431, no. 7, pp. 1315-1321, 2019.

[30] T. A. Mikropoulos and A. Natsis, "Educational virtual environments: A ten-year review of empirical research (1999–2009)," Computers & Education, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 769-780, 2011.

[31] Parong and R. E. Mayer, "Learning science in immersive virtual reality," Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 110, no. 6, p. 785, 2018.

[32] J. Zhao, L. Lin, J. Sun, and Y. Liao, "Using the summarizing strategy to engage learners: Empirical evidence in an immersive virtual reality environment," The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, vol. 29, pp. 473-482, 2020.

[33] F. Paas, A. Renkl, and J. Sweller, "Cognitive load theory and instructional design: Recent developments," Educational Psychologist, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 1-4, 2003.

[34] W. Schnotz and C. Kürschner, "A reconsideration of cognitive load theory," Educational Psychology Review, vol. 19, pp. 469-508, 2007.

[35] J. Sweller, J.J. Van Merrienboer, and F.G. Paas, "Cognitive architecture and instructional design," Educational Psychology Review, vol. 10, pp. 251-296, 1998.

[36] R.E. Mayer, Ed., The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

[37] J. Pape, T. Magdeldin, K. Stamati, A. Nyga, M. Loizidou, M. Emberton, and U. Cheema, "Cancer-associated fibroblasts mediate cancer progression and remodel the tumouroid stroma," British Journal of Cancer, vol. 123, no. 7, pp. 1178-1190, 2020.

[38] D. Matthews, "Virtual-reality applications give science a new dimension," Nature, vol. 557, no. 7703, pp. 127-128, 2018.

[39] S.K. Card, J. Mackinlay, and B. Shneiderman, Eds., Readings in Information Visualization: Using Vision to Think. Morgan Kaufmann, 1999.

[40] J.M. Pape, "Development of a 3D Biomimetic Tissue-Engineered Model of Cancer," Doctoral Dissertation, UCL (University College London), 2020.

[41] D. Bakkalci, "Development of a 3D Model of Ameloblastoma," Doctoral Dissertation, UCL (University College London), 2021.

[42] J. Zhao, L. Lin, J. Sun, and Y. Liao, "Using the summarizing strategy to engage learners: Empirical evidence in an immersive virtual reality environment," The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, vol. 29, pp. 473-482, 2020.

[43] D.A. Bowman and R.P. McMahan, "Virtual reality: how much immersion is enough?," Computer, vol. 40, no. 7, 2007.

[44] J.L. Plass and S. Kalyuga, "Four ways of considering emotion in cognitive load theory," Educational Psychology Review, vol. 31, pp. 339-359, 2019.

[45] A. Bangor, P.T. Kortum, and J.T. Miller, "An empirical evaluation of the system usability scale," Intl. Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 574-594, 2008.

[46] S.G. Hart and L.E. Staveland, "Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of empirical and theoretical research," in Advances in Psychology, vol. 52, pp. 139-183, North-Holland, 1988.

[47] L. Lin and M. Li, "Optimizing learning from animation: Examining the impact of biofeedback," Learning and Instruction, vol. 55, pp. 32-40, 2018.

[48] J.A. Holdnack and P.F. Brennan, "Usability and effectiveness of immersive virtual grocery shopping for assessing cognitive fatigue in healthy controls: protocol for a randomized controlled trial," JMIR Research Protocols, vol. 10, no. 8, p. e28073, 2021.

[49] J. Cohen, Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Academic Press, 2013.

[2] J. Pape, M. Emberton, and U. Cheema, "3D cancer models: the need for a complex stroma, compartmentalization and stiffness," Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, vol. 9, p. 660502, 2021.

[3] S. I. O'Donoghue, "Grand challenges in bioinformatics data visualization," Frontiers in Bioinformatics, vol. 1, p. 669186, 2021.

[4] S. Taylor and S. Soneji, "Bioinformatics and the Metaverse: Are we ready?," Frontiers in Bioinformatics, vol. 2, p. 50, 2022.

[5] A. V. Reinschluessel, T. Muender, D. Salzmann, T. Doering, R. Malaka, and D. Weyhe, "Virtual reality for surgical planning–evaluation based on two liver tumor resections," Frontiers in Surgery, vol. 9, p. 821060, 2022.

[6] D. Bressan, C. M. Mulvey, F. Qosaj, R. Becker, F. Grimaldi, S. Coffey, S. L. Vogl, L. Kuett, R. Catena, A. Dariush, and C. Gonzalez-Fernandez, "Exploration and analysis of molecularly annotated, 3D models of breast cancer at single-cell resolution using virtual reality," bioRxiv, pp. 2021-06, 2021.

[7] K. C. Cassidy, J. Šefčík, Y. Raghav, A. Chang, and J. D. Durrant, "ProteinVR: Web-based molecular visualization in virtual reality," PLoS computational biology, vol. 16, no. 3, p. e1007747, 2020.

[8] S. González Izard, R. Sánchez Torres, O. Alonso Plaza, J. A. Juanes Mendez, and F. J. García-Peñalvo, "Nextmed: automatic imaging segmentation, 3D reconstruction, and 3D model visualization platform using augmented and virtual reality," Sensors, vol. 20, no. 10, p. 2962, 2020.

[9] Bressan, C. M. Mulvey, F. Qosaj, R. Becker, F. Grimaldi, S. Coffey, S. L. Vogl, L. Kuett, R. Catena, A. Dariush, and C. Gonzalez-Fernandez, "Exploration and analysis of molecularly annotated, 3D models of breast cancer at single-cell resolution using virtual reality," bioRxiv, pp. 2021-06, 2021.

[10] Legetth, J. Rodhe, S. Lang, P. Dhapola, M. Wallergård, and S. Soneji, "CellexalVR: A virtual reality platform to visualize and analyze single-cell omics data," IScience, vol. 24, no. 11, 2021.

[11] F. Huettl, P. Saalfeld, C. Hansen, B. Preim, A. Poplawski, W. Kneist, H. Lang, and T. Huber, "Virtual reality and 3D printing improve preoperative visualization of 3D liver reconstructions—results from a preclinical comparison of presentation modalities and user’s preference," Annals of translational medicine, vol. 9, no. 13, 2021.

[12] I. Lau, A. Gupta, and Z. Sun, "Clinical value of virtual reality versus 3D printing in congenital heart disease," Biomolecules, vol. 11, no. 6, p. 884, 2021.

[13] K. A. Demidova and N. Markovkina, "Technologies of Virtual and Augmented Reality in Biomedical Engineering," in 2022 Conference of Russian Young Researchers in Electrical and Electronic Engineering (ElConRus), pp. 1496-1499, Jan. 2022.

[14] A. Elor, S. Whittaker, S. Kurniawan, and S. Michael, "BioLumin: An Immersive Mixed Reality Experience for Interactive Microscopic Visualization and Biomedical Research Annotation," ACM Transactions on Computing for Healthcare, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 1-28, 2022.

[15] E. Pajorová, L. Hluchý, I. Kostič, J. Pajorová, M. Bačáková, and M. Zatloukal, "A virtual reality visualization tool for three-dimensional biomedical nanostructures," in Journal of Physics: Conference Series, vol. 1098, no. 1, p. 012001, Sep. 2018.

[16] I. J. Akpan and M. Shanker, "A comparative evaluation of the effectiveness of virtual reality, 3D visualization and 2D visual interactive simulation: an exploratory meta-analysis," Simulation, vol. 95, no. 2, pp. 145-170, 2019.

[17] I. J. Akpan, M. Shanker, and R. Razavi, "Improving the success of simulation projects using 3D visualization and virtual reality," Journal of the Operational Research Society, vol. 71, no. 12, pp. 1900-1926, 2020.

[18] K. Betts, P. Reddy, T. Galoyan, B. Delaney, D. L. McEachron, K. Izzetoglu, and P. A. Shewokis, "An Examination of the Effects of Virtual Reality Training on Spatial Visualization and Transfer of Learning," Brain Sciences, vol. 13, no. 6, p. 890, 2023.

[19] W. Yin, "An artificial intelligent virtual reality interactive model for distance education," Journal of Mathematics, 2022, pp. 1-7.

[20] H. Roh, J. W. Oh, C. K. Jang, S. Choi, E. H. Kim, C. K. Hong, and S. H. Kim, "Virtual dissection of the real brain: integration of photographic 3D models into virtual reality and its effect on neurosurgical resident education," Neurosurgical Focus, vol. 51, no. 2, p. E16, 2021.

[21] J. Pape, T. Magdeldin, M. Ali, C. Walsh, M. Lythgoe, M. Emberton, and U. Cheema, "Cancer invasion regulates vascular complexity in a three-dimensional biomimetic model," European Journal of Cancer, vol. 119, pp. 179-193, 2019.

[22] H. K. Wu and P. Shah, "Exploring visuospatial thinking in chemistry learning," Science Education, vol. 88, no. 3, pp. 465-492, 2004.

[23] T. Timonen et al., "Virtual reality improves the accuracy of simulated preoperative planning in temporal bones: a feasibility and validation study," European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, vol. 278, pp. 2795-2806, 2021.

[24] L. Kuett et al., "Three-dimensional imaging mass cytometry for highly multiplexed molecular and cellular mapping of tissues and the tumor microenvironment," Nature Cancer, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 122-133, 2022.

[25] F. Biocca and B. Delaney, "Immersive virtual reality technology," Communication in the Age of Virtual Reality, vol. 15, no. 32, pp. 10-5555, 1995.

[26] C. Dede, "Immersive interfaces for engagement and learning," Science, vol. 323, no. 5910, pp. 66-69, 2009.

[27] A. Dengel and J. Mägdefrau, "Immersive learning explored: Subjective and objective factors influencing learning outcomes in immersive educational virtual environments," in 2018 IEEE International Conference on Teaching, Assessment, and Learning for Engineering (TALE), pp. 608-615, Dec. 2018.

[28] S. Schwan, "Digital pictures, videos, and beyond: Knowledge acquisition with realistic images," The Psychology of Digital Learning: Constructing, Exchanging, and Acquiring Knowledge with Digital Media, pp. 41-59, 2017.

[29] M. El Beheiry et al., "Virtual reality: beyond visualization," Journal of Molecular Biology, vol. 431, no. 7, pp. 1315-1321, 2019.

[30] T. A. Mikropoulos and A. Natsis, "Educational virtual environments: A ten-year review of empirical research (1999–2009)," Computers & Education, vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 769-780, 2011.

[31] Parong and R. E. Mayer, "Learning science in immersive virtual reality," Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 110, no. 6, p. 785, 2018.

[32] J. Zhao, L. Lin, J. Sun, and Y. Liao, "Using the summarizing strategy to engage learners: Empirical evidence in an immersive virtual reality environment," The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, vol. 29, pp. 473-482, 2020.

[33] F. Paas, A. Renkl, and J. Sweller, "Cognitive load theory and instructional design: Recent developments," Educational Psychologist, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 1-4, 2003.

[34] W. Schnotz and C. Kürschner, "A reconsideration of cognitive load theory," Educational Psychology Review, vol. 19, pp. 469-508, 2007.

[35] J. Sweller, J.J. Van Merrienboer, and F.G. Paas, "Cognitive architecture and instructional design," Educational Psychology Review, vol. 10, pp. 251-296, 1998.

[36] R.E. Mayer, Ed., The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

[37] J. Pape, T. Magdeldin, K. Stamati, A. Nyga, M. Loizidou, M. Emberton, and U. Cheema, "Cancer-associated fibroblasts mediate cancer progression and remodel the tumouroid stroma," British Journal of Cancer, vol. 123, no. 7, pp. 1178-1190, 2020.

[38] D. Matthews, "Virtual-reality applications give science a new dimension," Nature, vol. 557, no. 7703, pp. 127-128, 2018.

[39] S.K. Card, J. Mackinlay, and B. Shneiderman, Eds., Readings in Information Visualization: Using Vision to Think. Morgan Kaufmann, 1999.

[40] J.M. Pape, "Development of a 3D Biomimetic Tissue-Engineered Model of Cancer," Doctoral Dissertation, UCL (University College London), 2020.

[41] D. Bakkalci, "Development of a 3D Model of Ameloblastoma," Doctoral Dissertation, UCL (University College London), 2021.

[42] J. Zhao, L. Lin, J. Sun, and Y. Liao, "Using the summarizing strategy to engage learners: Empirical evidence in an immersive virtual reality environment," The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, vol. 29, pp. 473-482, 2020.

[43] D.A. Bowman and R.P. McMahan, "Virtual reality: how much immersion is enough?," Computer, vol. 40, no. 7, 2007.

[44] J.L. Plass and S. Kalyuga, "Four ways of considering emotion in cognitive load theory," Educational Psychology Review, vol. 31, pp. 339-359, 2019.

[45] A. Bangor, P.T. Kortum, and J.T. Miller, "An empirical evaluation of the system usability scale," Intl. Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 574-594, 2008.

[46] S.G. Hart and L.E. Staveland, "Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of empirical and theoretical research," in Advances in Psychology, vol. 52, pp. 139-183, North-Holland, 1988.

[47] L. Lin and M. Li, "Optimizing learning from animation: Examining the impact of biofeedback," Learning and Instruction, vol. 55, pp. 32-40, 2018.

[48] J.A. Holdnack and P.F. Brennan, "Usability and effectiveness of immersive virtual grocery shopping for assessing cognitive fatigue in healthy controls: protocol for a randomized controlled trial," JMIR Research Protocols, vol. 10, no. 8, p. e28073, 2021.

[49] J. Cohen, Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Academic Press, 2013.

3.2 Information:

-

Allen Cell Explorer (https://www.allencell.org/)

-

Virtual reality journey through a tumour (https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/virtual-reality-journey-through-a-tumour-cambridge-scientists-receive-ps40-million-funding-boost)

-

CANCER RESEARCH HORIZONS_Innovation & Entrepreneurship Awards (https://www.cancerresearchhorizons.com/innovation-entrepreneurship-awards-2022)

-

CANCER GRAND CHALLENGES_An entirely new way to visualise tumours (https://cancergrandchallenges.org/news/entirely-new-way-visualise-tumours

3.3 Industry-related companies:

- Nanome (https://nanome.ai/)

- BioHues Digital (https://biohuesdigital.com/)

-

Now Medical Studios (https://www.nowmedicalstudios.com/)

-

Fusion Medical Animation (https://www.fusionanimation.co.uk/)

3.4 Video:

-

Using Orthogonal Views in ImageJ/Fiji & Imaris (https://youtu.be/94d8sHMP_w8)

- Tumour mapping in Virtual Reality (https://youtu.be/mZI5fJLOXoA)

- A virtual reality journey through a tumour ((https://youtu.be/PavWaFWeNII)