"Does the skin of AI bear any scars?"

In the "Trauma Doll" project, I further probed the vitality of artificial intelligence and its communicative relationship with humans. Traces on the skin attest to humans as life forms with experiences and concepts of time.

Every moment, every breath, every heartbeat in human life creates an experience and shapes the individual. However, AI, regardless of the complexity of its algorithms or the volume of data it handles, cannot truly experience life. Its "experience" is simulated through algorithms and data, not a genuine life experience. This led me to raise such questions: can these data generated by algorithms be considered a form of life? Should we grant them the right to life? Can the 'skin' of AI bear any 'scars?'

During an accidental incident, I unintentionally injured my knee (see left image). Although falls are not uncommon in daily life, this event became a memorable experience for me due to my long absence from such occurrences. I recorded the process of this injury and began to delve into the characteristics of the skin, reviewing my personal experiences and various common signs on the skin.

This unusual experience sparked a deep fascination with the uniqueness of human skin. As I witnessed the gradual healing of my injured knee, I marvelled at the resilience and regenerative abilities of the skin. I realized that the skin is not just a protective layer of our body; it is an incredibly complex biological system with self-healing capabilities and adaptability to environmental changes. This experience triggered my curiosity about the skin. I began to study various characteristics of the skin, exploring how the skin responds to changes in the external environment and the role of skin in various functions of our body. I noticed that the frequent marks on the skin, such as scars, spots, and textures, are historical records of skin experiences, revealing our past.

Human skin

As the first line of defence in humans, skin constitutes a complex and remarkable system, effectively shielding us against environmental stressors such as ultraviolet radiation, pathogenic invasion, and mechanical injury. However, when these stressors exceed the skin's capacity to cope, pathological changes may ensue. Beyond its role as a passive defence system, skin also serves as an active sensorial organ, endowed with the ability to perceive, relay information, and adapt to environmental changes. Skin regulates body temperature by adjusting blood flow, expels excess heat and waste through increased sweat gland secretion, perceives external threats via pain and tactile sensations, and can even function as a communicative signal.

When skin lesions occur, changes in colour, shape, and texture often result, typically due to changes in pigment production, particularly melanin, which is produced by melanocytes in the skin. In certain skin lesions, such as melanoma (a type of skin cancer), melanocytes grow out of control, leading to an excess of pigment that darkens the skin colour. On the other hand, certain lesions (such as vitiligo) may lead to a reduction in melanocytes, lightening the skin colour. Morphological changes are caused by the proliferation or reduction of cells in the skin layers. For instance, squamous cell skin cancer is caused by the overgrowth of squamous cells in the skin's epidermis, which may result in hard lumps, ulcers, or scaly structures on the skin's surface. Certain viruses can also cause skin cells to overgrow, forming visible protrusions. In some cases, skin lesions may further develop into cancer.

The onset of skin cancer usually starts with damage to the DNA of skin cells. This damage can come from many sources, including ultraviolet radiation (such as sunlight and fluorescent lights), harmful chemicals, viral infections, or genetic factors. Once a cell's DNA is damaged, it may start to proliferate abnormally. This is usually because the damage affects the regulation of the cell cycle, causing the cell to divide and grow excessively. As the abnormal cells increase, they may form a tumour. The tumour could be benign (i.e., it won't spread to other parts) or malignant (i.e., it can invade surrounding tissues and possibly metastasize to distant parts). If the tumour is malignant, it may invade the surrounding tissues and metastasize to other parts of the body through the blood or lymphatic system. This stage is called metastasis, typically the most dangerous stage of skin cancer, as it can affect other organs in the body. Notably, the process of skin cancer usually takes a long time, potentially spanning several years or even decades.

Human skin cancer dataset+DCGAN

/

In the book "Leather Without Victims," I came to understand that the boundaries between organisms and inorganic matter are not absolute. This sparked my reflection on a question: if we use algorithms to generate a large amount of data on human skin lesions, could this data be considered a life? Should they enjoy the right to life? Does this existence, which lies between life and non-life, suggest that the concept of "life" in a post-human context can be quantified, divided, or reassembled?

We know that hybrids of machines and organisms consist of silicon and carbon elements. Between these two exists a channel for information flow, allowing interaction between carbon-based organisms and silicon-based inorganics, thereby enabling carbon and silicon to operate in the same system. From a cybernetic perspective, they consider the embodiment of life as merely a very short stage in the continuum of life. They believe that life can exist independently of the physical body. They propose that life is fundamentally an information channel, a computational pattern of information.

We know that hybrids of machines and organisms consist of silicon and carbon elements. Between these two exists a channel for information flow, allowing interaction between carbon-based organisms and silicon-based inorganics, thereby enabling carbon and silicon to operate in the same system. From a cybernetic perspective, they consider the embodiment of life as merely a very short stage in the continuum of life. They believe that life can exist independently of the physical body. They propose that life is fundamentally an information channel, a computational pattern of information.

In 2019, the Getty Conservation Institute initiated a forum named "Living Matter”, aiming to broadly discuss the challenges faced by works using biological materials in the contemporary art field. Eduardo Kac, a Brazilian-American artist, first introduced the concept of bio-art manipulating life in his 1997 work, "Time Capsule." He believes that bio-art can not only create new objects but may also create new subjects.

From the previous study on the skin, we know that human skin is a precious and complex organ, as well as the largest organ in the human body. By studying how the skin reacts under different environmental conditions or changes under certain disease states, we can reflect a person's overall health status. Visually, it includes changes in colour, shape, and texture. By using the DCGAN (Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks) deep learning model to analyze skin lesion data, theoretically, we can discuss the information channels between carbon-based organisms and silicon-based electronic components, and how they operate within a system. From a machine's perspective, we observe the morphology and process of human skin lesions, exploring how bio-art controls organic tissue organs and their relationships.

Trauma Doll

/

The traces on the skin affirm that humans are living beings with experiences and concepts of time. Every moment of human life, every breath, every heartbeat, creates experiences and shapes individuals. However, AI, no matter how complex its algorithms are or how large the amount of data it processes, cannot truly experience life. Its "experience" is simulated through algorithms and data, not a genuine life experience.

![]()

For further exploration of this theme, I need to shift my perspective to the fields of artificial intelligence and deep learning, using DCGAN (Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks) to process and generate skin lesion data. DCGAN, by receiving a large amount of skin lesion data, learns the basic characteristics of the skin, including changes in colour, shape, texture, etc., and thus generates realistic skin lesion images during the training process. It's not just a visualization of the process of skin lesions, I am considering – can these data generated by algorithms be regarded as a form of life? Can we grant them life rights? Is their "epidermis" also traumatized? By opening the carbon-silicon information channel through deep learning, we have the opportunity to examine and understand the communication relationship between organic bodies (carbon-based) and silicon-based life forms from a completely new perspective. These are questions worth delving into. At the same time, this may provide valuable thinking for us to further understand the essence of life.

For further exploration of this theme, I need to shift my perspective to the fields of artificial intelligence and deep learning, using DCGAN (Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks) to process and generate skin lesion data. DCGAN, by receiving a large amount of skin lesion data, learns the basic characteristics of the skin, including changes in colour, shape, texture, etc., and thus generates realistic skin lesion images during the training process. It's not just a visualization of the process of skin lesions, I am considering – can these data generated by algorithms be regarded as a form of life? Can we grant them life rights? Is their "epidermis" also traumatized? By opening the carbon-silicon information channel through deep learning, we have the opportunity to examine and understand the communication relationship between organic bodies (carbon-based) and silicon-based life forms from a completely new perspective. These are questions worth delving into. At the same time, this may provide valuable thinking for us to further understand the essence of life.

Technical Implementation

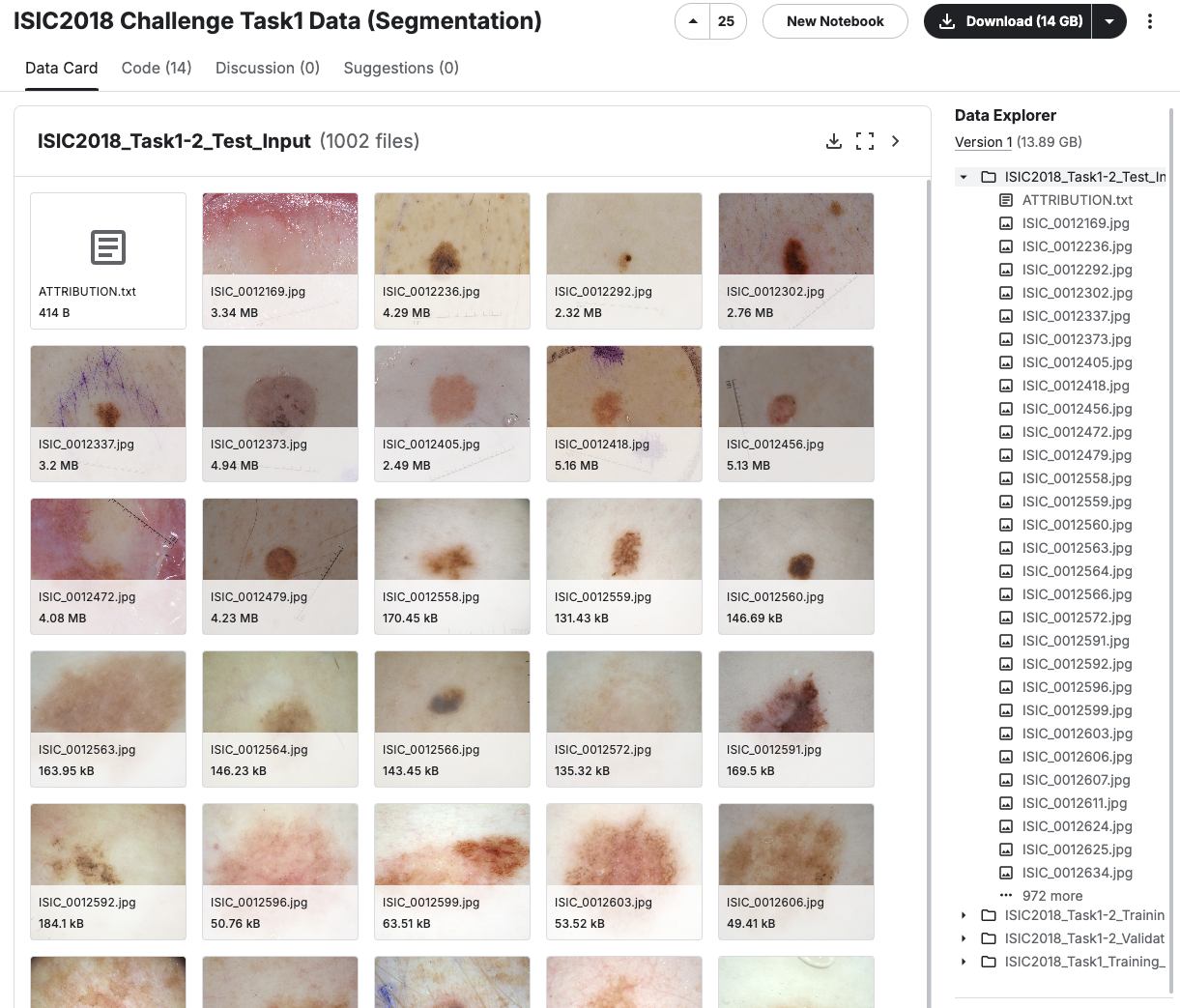

Data Source: ISIC2018 Challenge Task1 Data (Segmentation) (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/tschandl/isic2018-challenge-task1-data-segmentation).

Sample Size: 962

1. Data Collection: A dataset of skin cancer images was collected. This dataset should contain a variety of types of skin cancer images, such as melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma. (The data collection process adheres to all legal and ethical guidelines, and respects all privacy rules.)

2. Data Preprocessing: The images were preprocessed so that they could be input into the DCGAN model. This might include resizing images (adjusting them to 512*512), normalizing colour values, etc. To generate more consistent and high-quality images, it was also necessary to manually filter the data and remove blurry or poor-quality images.

3. Training the DCGAN Model:

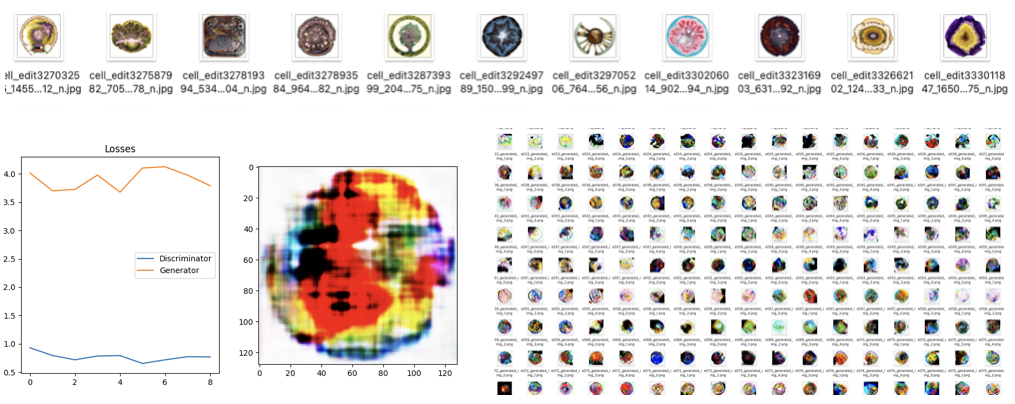

3.1 A Failed Attempt

I implemented the Generative Adversarial Network using PyTorch. The generator network is composed of multiple ConvTranspose2d (Transpose Convolutional) layers, combined with BatchNorm2d (Batch Normalization) and ReLU activation functions. The final layer uses a ConvTranspose2d layer, followed by a Tanh activation function, to generate the output image. The discriminator network consists of multiple Conv2d (Convolutional) layers, combined with Batch Normalization, LeakyReLU activation function, and a Sigmoid activation function (located in the output layer).

However, this attempt failed, and the final images generated were not satisfactory.

However, this attempt failed, and the final images generated were not satisfactory.

3.2 Implementing GAN with TensorFlow — Successful!

The TensorFlow 2. x APIs, including tf. Keras and tf.GradientTape, were used. During the training process, adjustments were made to the discriminator and generator losses for each batch in each epoch, along with the learning rate, noise size, model save interval, etc. In total, the model was trained 11 times, generating 2479 and 11806 images respectively (totalling 41.1GB).

![]()

4. Generating Images:

![]()

The colour, texture, and appearance of the skin can greatly impact the visual effect and emotional perception of a person or a character.

By utilizing DCGAN and training it with a dataset of skin lesions, including those with prominent cancerous features, I was pleasantly surprised to observe that the AI model showcased the progression of human skin diseases. In my eyes, it seemed as though the AI itself was experiencing these pathological changes, transitioning from a blood-red colour to a bruised purple, then to a greenish-yellow hue, and ultimately turning completely black.

The colour, texture, and appearance of the skin can greatly impact the visual effect and emotional perception of a person or a character.

By utilizing DCGAN and training it with a dataset of skin lesions, including those with prominent cancerous features, I was pleasantly surprised to observe that the AI model showcased the progression of human skin diseases. In my eyes, it seemed as though the AI itself was experiencing these pathological changes, transitioning from a blood-red colour to a bruised purple, then to a greenish-yellow hue, and ultimately turning completely black.

5. Artistic Creation:

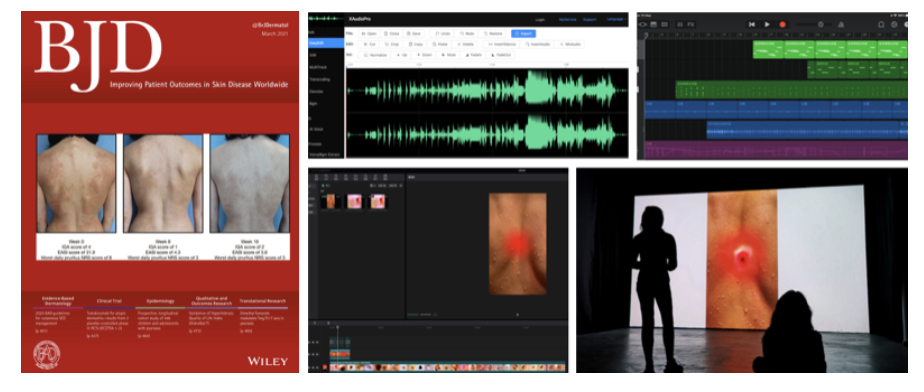

Inspired by a cover of the British Journal of Dermatology, I captured footage of the healthy skin on my back and composed a musical score to accompany it.

Through creative editing and synthesis, I created an experimental video that merges the visual imagery of my healthy skin with the auditory elements of the musical composition.

![]()

Inspired by a cover of the British Journal of Dermatology, I captured footage of the healthy skin on my back and composed a musical score to accompany it.

Through creative editing and synthesis, I created an experimental video that merges the visual imagery of my healthy skin with the auditory elements of the musical composition.

6. Future development:

1. Technological Advancement: Continue researching and improving DCGAN and other related deep learning algorithms to enhance their performance in handling and generating skin lesion data. Additionally, explore more deep learning models and new learning strategies to achieve breakthroughs in simulating life processes and understanding life characteristics. Initializing weights in a specific way is very important!!

2. Ethical and Societal Implications: I will focus on studying and researching this project's potential ethical and societal impacts. For example, how would assigning life rights to algorithmically generated data affect our ethical views and legal regulations? Or, how would the ability to quantify, segment, or reassemble life impact our society, culture, and even our self-perception?

3.Exploration of the Boundary between Life and Non-life: Through the analysis of deep learning and skin lesion data, I will attempt to blur the boundary between life and non-life. I will continue to explore whether the data generated by algorithms can be considered a form of life and whether we can grant them life rights. At the same time, we will consider how to define and evaluate the "experience" and "perception" of AI.

1. Technological Advancement: Continue researching and improving DCGAN and other related deep learning algorithms to enhance their performance in handling and generating skin lesion data. Additionally, explore more deep learning models and new learning strategies to achieve breakthroughs in simulating life processes and understanding life characteristics. Initializing weights in a specific way is very important!!

2. Ethical and Societal Implications: I will focus on studying and researching this project's potential ethical and societal impacts. For example, how would assigning life rights to algorithmically generated data affect our ethical views and legal regulations? Or, how would the ability to quantify, segment, or reassemble life impact our society, culture, and even our self-perception?

3.Exploration of the Boundary between Life and Non-life: Through the analysis of deep learning and skin lesion data, I will attempt to blur the boundary between life and non-life. I will continue to explore whether the data generated by algorithms can be considered a form of life and whether we can grant them life rights. At the same time, we will consider how to define and evaluate the "experience" and "perception" of AI.

Reflection

Reflection:

Actually, before settling on this theme, I had planned to use cell images as a dataset for my artwork. However, after struggling with debugging for a long time, I couldn't achieve the desired results. I intend to revisit this theme and continue experimenting with it in the future.

Actually, before settling on this theme, I had planned to use cell images as a dataset for my artwork. However, after struggling with debugging for a long time, I couldn't achieve the desired results. I intend to revisit this theme and continue experimenting with it in the future.

In general, although I, as a human, am the one training the computer with images, I believe that AI might be a mixture of machine and organism, a blend of silicon and carbon elements. This artwork represents the process of bio-art manipulating life. Bio-art not only creates new objects but also creates new subjects. After the development of biotechnology, there is no absolute boundary between organisms and inorganic matter. From my perspective, the images generated by DCGAN on the screen are constantly transforming themselves, gradually evolving into forms that resemble humans and carry recognizable interpretations of human activities.

Everything presented by AI is based on the guidance I provide to the computer. It is in a constant state of transformation, creation, and non-self-creation, immersed in the flow of creativity. AI's understanding and perception of the world are both strange and beautiful, providing us with a new perspective on the inherent vision of artificial intelligence. It is a behind-the-scenes glimpse into the algorithms that ordinary people cannot comprehend. Just as humans only know what they have learned or experienced, artificial intelligence also evolves through training. When creating artificial intelligence, we can selectively limit AI's learning of specific knowledge.

However, the problem lies in this "selective knowledge." How do we coexist with machines that inherently lack human values? Artificial intelligence does not possess human values, and what may be obvious to humans may not be explicitly programmable. What values should we embed in AI? If humans cannot even reach a consensus on cross-cultural values, how can we teach a machine to act for our greatest benefit universally? Can we teach AI ethics, empathy, or compassion? How can we teach AI moral standards that are correct but not effective? Moreover, moral standards vary across cultures and evolve. Given all this, how should we train AI? How can we ensure that the datasets used to train AI are fair and balanced...

Everything presented by AI is based on the guidance I provide to the computer. It is in a constant state of transformation, creation, and non-self-creation, immersed in the flow of creativity. AI's understanding and perception of the world are both strange and beautiful, providing us with a new perspective on the inherent vision of artificial intelligence. It is a behind-the-scenes glimpse into the algorithms that ordinary people cannot comprehend. Just as humans only know what they have learned or experienced, artificial intelligence also evolves through training. When creating artificial intelligence, we can selectively limit AI's learning of specific knowledge.

However, the problem lies in this "selective knowledge." How do we coexist with machines that inherently lack human values? Artificial intelligence does not possess human values, and what may be obvious to humans may not be explicitly programmable. What values should we embed in AI? If humans cannot even reach a consensus on cross-cultural values, how can we teach a machine to act for our greatest benefit universally? Can we teach AI ethics, empathy, or compassion? How can we teach AI moral standards that are correct but not effective? Moreover, moral standards vary across cultures and evolve. Given all this, how should we train AI? How can we ensure that the datasets used to train AI are fair and balanced...

References

Literature:

Machine Ethics (Edited by Michael Anderson, University of Hartford, Connecticut, Susan Leigh Anderson, University of Connecticut)

Wallach, Wendell, and Colin Allen, Moral Machines: Teaching Robots Right from Wrong (New York, 2009; online edn, Oxford Academic, 1 Jan. 2009), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195374049.001.0001, accessed 4 May 2023.

Noel Codella, Veronica Rotemberg, Philipp Tschandl, M. Emre Celebi, Stephen Dusza, David Gutman, Brian Helba, Aadi Kalloo, Konstantinos Liopyris, Michael Marchetti, Harald Kittler, Allan Halpern: “Skin Lesion Analysis Toward Melanoma Detection 2018: A Challenge Hosted by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC)”, 2018; https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.03368

Dobre, G.C., Gillies, M. & Pan, X. Immersive machine learning for social attitude detection in virtual reality narrative games. Virtual Reality 26, 1519–1538 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-022-00644-4

Malevé, N. On the data set’s ruins. AI & Soc 36, 1117–1131 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01093-w

Radivojević, T., Costello, Z., Workman, K. et al. A machine learning Automated Recommendation Tool for synthetic biology. Nat Commun 11, 4879 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18008-4

Ratushny, V., Gober, M. D., Hick, R., Ridky, T. W., & Seykora, J. T. (2012). From keratinocyte to cancer: the pathogenesis and modelling of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of clinical investigation, 122(2),464-472. www.jci.org/articles/view/57415

Karimkhani, C., Green, A. C., Nijsten, T., Weinstock, M. A., Dellavalle, R. P., Naghavi, M., & Fitzmaurice, C. (2017). The global burden of melanoma: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. British Journal of Dermatology, 177(1), 134-140. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15510

Leiter, U., & Garbe, C. (2008). Epidemiology of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer—the role of sunlight. In Sunlight, Vitamin D and Skin Cancer (pp. 89-103). Springer, New York, NY. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-0-387-77574-6_8

Information:

- Data-Centric AI vs. Model-Centric AI (https://dcai.csail.mit.edu/lectures/data-centric-model-centric/)

- My journey through GANs for Pokemon Generation (https://medium.com/@arhamsmita/my-journey-through-gans-for-pokemon-generation-c8662de64a1d)

- Generative Adversarial Networks 101(https://towardsdatascience.com/generative-adversarial-networks-101-c4b135a440d5)

- GANs — What and Where? (https://medium.com/thecyphy/gans-what-and-where-b377672283c5)

- Why Computers Do Not Make Art (https://medium.com/@aaronhertzmann/why-computers-do-not-make-art-6c7f9bff6b04)

- PUTTING PEOPLE IN CLASSIFICATORY BOXES (https://networkcultures.org/longform/2020/06/22/on-the-basis-of-face-biometric-art-as-critical-practice-its-history-and-politics/)

- Systemic Errors of Collective Intelligence. A Conversation with Agnieszka Kurant (https://flash---art.com/article/agnieszka-kurant/)

- Creative Machine Oxford Symposium 2023 (https://www.creativemachine.io/)

- Art illuminates the beauty of science – and could inspire the next generation of scientists young and old (https://theconversation.com/art-illuminates-the-beauty-of-science-and-could-inspire-the-next-generation-of-scientists-young-and-old-168925)

- Biomedical wonders brought to life in Art of Science exhibition (https://www.wehi.edu.au/news/biomedical-wonders-brought-life-art-science-exhibition)

Dataset:

- ISIC2018 Challenge Task1 Data (Segmentation) (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/tschandl/isic2018-challenge-task1-data-segmentation)

Tool:

- Keras (https://keras.io/examples/generative/gaugan/)

- Instance Noise: A trick for stabilising GAN training (https://www.inference.vc/instance-noise-a-trick-for-stabilising-gan-training/)

- How to Train a GAN? (https://github.com/soumith/ganhacks/blob/master/README.md)

- Art-using-GANs (https://github.com/Kaustubh1Verma/Art-using-GANs/tree/ff41eeb5099d2aa3976ed1f051596d14015548d5)

Projects:

- A guy trained a machine to "watch" Blade Runner. Then things got seriously sci-fi. (https://www.vox.com/2016/6/1/11787262/blade-runner-neural-network-encoding)

Video:

- DCGAN with CelebA: Full training time-lapse (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nkbgbo2s95o)

- Artist+AI Lecture: Figures and Form (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TN7Ydx9ygPo)